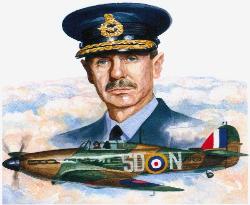

A historian once declared that Hugh Dowding, Air Chief Marshall and head of RAF Fighter Command was “the only commander who won one of the decisive battles of history, and got sacked for his pains.”[1] Shortly after his successful defense of England in the Battle of Britain, Dowding was forcibly retired in a move which many, himself

included, felt was more personal than anything else, the final victory of those whose pride had been wounded by the undiplomatic man who had been head of RAF Fighter Command. Dowding was known to be difficult and determined, unwavering in the face of opposition when he knew himself to be right. These attributes brought a career in its twilight to a rapid and unceremonious close, but they also enabled him to successfully defend England in the summer of 1940. In spite of the obstinacy which made him so unpopular, Dowding’s single-minded stubbornness and unwavering confidence in his own judgement ensured that England was equipped with the tactics and technology necessary to defend herself successfully during the Battle of Britain.

A Woefully Brief Summary of the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain is typically divided into three stages, followed by the London Blitz. Sure that the British had nothing to defend themselves with – so much had been left on the beaches of Dunkirk following the Battle of France – Hermann Goering bragged to Hitler that he could defeat the RAF in just three days. However, clever deception and good preparation on behalf of Dowding would prove Goering wrong as the battle stretched for weeks and months, and finally the invasion of England had to be called off entirely.

Opening on July 10th, 1940, the first stage of battle is known as Kanalkamph, the Channel Battle, and had four goals: destroy the Royal Air Force, strangle shipping, terror bomb if necessary, and after air superiority had been achieved proceed with landing and invasion.[2] Given that the British pilots were not prepared to fight over water and were often outnumbered, British losses at this stage of the battle were high. [3] The Germans caused so much damage that shipping was first switched from day to night, and finally had to be sent by rail. However, the Luftwaffe failed to achieve air superiority and Goering’s brag had already been disproven. Frustrated, he changed tactics.

Initially delayed by bad weather, the second phase of the Battle of Britain was launched August 12th. The purpose of Adlerangriff – Attack of the Eagles – was to focus on the coastal airfields so the way for invasion could be made ready.[4] The first stage of attack was designed to blind the RAF by taking out the radar stations.[5] This they failed to do, and whatever minor damage they had managed on that first morning was remedied by afternoon.[6] The RDF stations would be hit several more times that week, but a failure to cut the phone lines connecting them meant that they remained operational. This was a critical failure on behalf of the Luftwaffe, as the RDF stations were vital in getting the RAF in the air to meet the Luftwaffe. Fighting intensified between August 24th and September 6th. This was a critical time in the Battle of Britain, as for the first time the British were unable to make up their losses and the RAF was forced to tap Dowding’s precious reserve of planes. At this time, had the Germans continued to hammer England at such a brutal pace for another three weeks it is sure she would have faltered and lost.[7] However, faulty intelligence saved the day. Believing Dowding to be critically weakened, Goering shifted his focus to London, hoping to draw out the elusive “last few planes” in a final, killing battle that would cripple the Royal Air Force.[8]

In early September the Luftwaffe turned their planes on London, abandoning the airfield attacks. Once again, air superiority had not been achieved. However, the Germans received a nasty shock as the RAF, far more powerful than Goering had suspected, met them with full strength and routed them over London on September 15th, the day now

known as Battle of Britain day. Outnumbered nearly two to one, the British inflicted heavy losses on the Germans – sixty-one planes plus another twenty damaged beyond flight capacity. The British lost thirty-five.[9]

The heavy losses of September 15th would force another change in strategy, and the Luftwaffe would begin bombing at night. The Battle of Britain was over. The Blitz had begun, but fifty-seven consecutive nights of bombing failed to induce the British to surrender. Frustrated, Hitler turned towards Russia, leaving some of the Luftwaffe to continue the harassment of the British while moving the rest of the Eastern Front. This mistake would prove fatal not only because Operation Barbarossa was to prove the beginning of Hitler’s end, but also because a free and independent England would later provide the springboard for invasion and liberation of the European continent by the Allied powers. However, controversy over Dowding’s strategy combined with his inability to protect London at night led to the end of his career, and he was forcibly retired in October of 1940.

Dowding’s Contributions

Affectionately dubbed “Ol’ Stuffy” for his quiet reserve and Victorian manners, Hugh Cashwell Tremenhere Dowding was actually a forward thinking man with a fascination for new gadgets and a clear vision of their possible uses. While his peers and superiors remained entrenched in theory which was growing increasingly outdated, Dowding embraced the technological advances of the early twentieth century and began pushing the boundaries of classical military thought as early as his entry to staff college in 1912. While naysayers continually dogged his steps, Dowding persevered and not only shaped air war during the Great War, he went on to provide England with invaluable tools including radar, a complex defense network, legendary fighter planes, and tactics and strategy which would prove successful against the German onslaught in the summer of 1940. Without Dowding’s foresight, stubbornness, and confidence, England would have foundered.

Aerial Warfare

Starting with a training exercise in Staff College in 1913, Dowding discovered six unused airplanes and, against the advice of his instructors, used the planes to observe his opponents’ movements and consequently won the exercise.[10] From this experience he took a deep faith in the value of flight. When war broke out a year later, Dowding was sent to France to conduct aerial observations over the enemy. It was from these observation flights that air warfare was born. The observation pilots used to wave at each other when they passed, but then one day someone threw a rock instead of waving and soon they were shooting at each other.[11] Bombing military targets from the air was a natural progression, and this in turn would evolve into the bombing of civilian targets and eventually to terror bombing. All this was made possible through Dowding’s simple belief in the usefulness of flight for observation at a time when airplanes were considered gadgets and no one else was quite sure what to do with them in a martial setting. Dowding was also the first in England and perhaps the world to use air-to-ground radio to communicate.[12] However, true to the technophobia and truculence which Dowding had discovered in Staff College, there were those who immediately condemned putting radio in planes as “cheating.”[13]

Research and Development

During the interwar period Dowding not only achieved the rank of Air Vice Marshall for the nascent RAF but also became involved in Supply and Research, an ideal position for a technophile such as he. This position allowed him to provide the growing RAF with the technology which would protect them against the Luftwaffe in 1940, such as radar and monowing fighter planes like the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane.

Even the creation of a fighter wing for the RAF met with opposition. Following the terror bombing of the Great War, most commanders and air theorists believed “the bomber (would) always get through.”[14] Defense was thought impossible because there was simply no way to detect the arrival or location of incoming bombers in time to get a fighter up to defend against them. Instead, air forces emphasized building bigger and better bombers. Dowding, however, was not content with this idea and sought ways to prevent the bomber from striking at all. He needed two things to do this – sufficient fighters that could lie in wait for the bombers, and an early warning system that would make it possible to detect said bombers and therefore have the fighters prepped and ready.[15] He would spend the next decade making this goal a reality and in turn, save England.

To achieve this goal, England would have to build a fighter that could match the speeds and altitudes of the new bomber planes. Looking to single wing racing planes, Dowding convinced a reluctant Ministry to adopt a design for a closed-cockpit, single-wing airplane with a powerful engine. The Ministry was reluctant, preferring to trust in the old, reliable bi-plane and failing to consider the advances made in plane material. However, Dowding once again prevailed and the eight-gunned Supermarine Spitfire was born.[16] Also produced was the Hawker Hurricane, slower than the Spitfire but an able fighter all the same.[17] In 1935, Dowding found an ally in Chancellor Neville Chamberlain who supported the expansion of the air force. [18] Stuffy began building squadrons of fighter planes, declaring confidently that “The best defense of the country is the fear of fighter.”[19]

Next he needed a way to detect incoming bombers so that his fighters could be in the right place at the right time to stop them. In that same year he found his answer thanks to a scientist named Robert Watson-Watt, who demonstrated what was then known as Radio Direction Finding, or RDF, to the Air Marshall. In spite of Churchill’s preference for research on a death-ray, Dowding authorized funding for the project immediately. By 1937, 20 radar stations had been built and were accurately detecting aircraft from over 100 miles away.[20]

The RDF chains were to be a piece of a greater whole that became known as the Dowding System, the world’s first ground-controlled interception network. Dowding established the Royal Observer Corp to bolster the information obtained from the RDF stations.

Building a vast telephone network with buried landlines, information from the RDF and the ROC would be phoned into Fighter Command and plotted on a giant map of England to give them a thorough picture of what was happening in British airspace.[21] Dowding’s fighters and anti-aircraft artillery could then be alert and ready for approaching German bombers.

Rotation

Also vital to British success was Dowding’s regard for his pilots, whom he affectionately called his “chicks.” The Germans, in true Prussian manner, expected their pilots to be machines and gave them no breaks. Straight from France into the Battle of Britain, German pilots began to suffer from a form of battle fatigue that became known as Kanalkrankheit – Channel Sickness. Dowding, on the other hand, provided for the human element in his pilots as far back as his command in the Great War. In 1916 he was made Lieutenant Colonel of a fighter squadron in France. When his concern for his exhausted troops became too big of a nuisance, his commander Hugh Trenchard made him a Brigadier General in order to get him out of the way and sent him back to England.[22] Yet even here the two men would butt heads. Trenchard needed pilots, and fast. Dowding, however, refused to send hastily and poorly trained pilots unprepared to the slaughter. Trenchard rewarded him for his stubbornness in 1918 by dismissing him and sending him back to the artillery, where he had begun.[23]

In spite of the trouble it had caused him in the previous war, Dowding continued to look out for his chicks’ well-being. Realizing that in July 1940 accidents accounted one-third of their losses, Stuffy insisted on rest for his pilots. Each pilot would receive eight hours of rest daily and 24 hours leave weekly.[24] He also established a system of rotation, having pilots serve for three weeks in once sector before being moved to another. This allowed weary pilots who were assigned heavily hit areas in the south a period of relative rest. Also, he started new pilots in the north so that they had more time to practice and become familiar with their machines before being sent into the meat grinder.[25]

Strategy: The Big Wing Controversy

Although his technophilia and his regard for his chicks had caused him trouble with superiors all throughout his career, the controversy which would ultimately result in his dismissal centered around the strategy he used during the Battle of Battle.

Following the Battle of France, the British Expeditionary Force were hurriedly evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk and forced to leave much of their kit behind. The Germans believed that the British were now fighting on little more than English pride. The opposite was true; in the interim between the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain, the British were very busy preparing their beaches and the home guard to defend, and Dowding had a handsome stockpile of fighter planes which he had carefully and stubbornly withheld from action in France – an action which angered Churchill, who believed the war could be decided in France. Dowding, however, had foreseen the collapse of their continental and insisted on preserving every plane possible, especially his precious Spitfires, for the coming defense of England.

The strategy he devised to face the Germans was simple: defend and deceive. All England had to do was hold off the Nazis until bad fall weather brought rains and a rough Channel, thus making invasion impossible.[26] The Germans assumed that the British had very little with which to defend themselves and expected an easy fight. Dowding intended to exploit this perceived weakness to his benefit, and so throughout the battle would only dispatch small groups of fighters instead of entire squadrons. This Penny Packet strategy would not only serve to protect his pilots and aircraft, it would also deceive the Nazis about the true strength of the RAF and cause them to underestimate the British. Goering would be left to assume that the Royal Air Force was weak and waning, and with luck, his famous ego would be his undoing

Not everyone agreed with Dowding, especially the ambitious Air Vice Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory. Intent on undermining Dowding for the sake of advancing his own career, Leigh-Mallory repeatedly defied Dowding’s order for Penny Packets. Instead, he scrambled entire squadrons in the Big Wing formation. These Big Wings, while impressive, were slow to scramble and nearly always arrived too late to do any good.[27] They were also not as effective as Leigh-Mallory led Churchill and the Air Ministry to believe – the chaos caused by fighting in this formation led pilots to double-count their kills, creating the impression that the tactic was far more successful than it really was.[28] However, in mid-October Leigh-Mallory was able to convince the Air Ministry to call Dowding before them. Here Stuffy faced questioning over his failure to prevent the Blitz and his handling of the day-time attacks, in spite of the fact that his tactics had successfully prevented invasion. The Big Wing controversy had been brought to the fore by Leigh-Mallory and other political enemies whose ambitions were blocked by the commanding officers in question. Insisting that Big Wings were superior, Leigh-Mallory blamed his consistent failure to arrive at battle on time on not being given enough notice, even though he received his orders simultaneously with other commanders who were able to arrive on time.[29] In the end, the Ministry declared that Dowding and his right hand man Keith Park had been in error to rely on their Penny Packets.[30] Both men were soon relieved of duty. Sholto Douglas, one the pilots who had instigated the meeting, was given Dowding’s position, and Leigh-Mallory replaced Keith Park.

Although he had been putting off retirement in order to protect England from Germany, Dowding felt ill-abused by this unceremonious dismissal, the result not of incompetence but of unwillingness to accede to the opinion of others when he knew himself to be right. For the next several decades, he was generally overlooked by history in spite of his vital contributions towards preventing German hegemony in Europe, only beginning to gain just recognition in recent years. A weaker man, a less stubborn man, would have capitulated to the demands of diplomacy and England would have languished before the Germans without the indispensable tools which only Air Marshall Hugh Dowding could provide.

Bibliography

Braun, Simon. “The Command Style and Competence of Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Caswell Tremenheere Dowding.” Master’s thesis, University of Canberra, 2005.

Bungay Stephen. The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain. London: Aurum Press, 2000.

Clode, George. “Dowding and Park: Air War’s Greatest Commanders?” http://www.military-history.org/articles/dowding-and-park-air-wars-greatest-commanders.htm (accessed April16, 2013).

Fischer, David. A Summer Bright and Terrible: Winston Churchill, Lord Dowding, Radar, and the Impossible Triumph of the Battle of Britain. California: Counterpoint Press, 2006.

Holland, James. The Battle of Britain: Five Months that Changed History, May-October 1940. New York: Macmillan, 2012.

Wright, Robert. The Man Who Won the Battle of Britain. New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1969.

Probert, Henry. Bomber Harris: His Life and Times. London: Greenhill Books, 2006.

Richards, Denis, and Hilary St. G. Saunders. Royal Air Force, 1939-194,Vol I: The Fight at Odds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953.

Price, Alfred. The Hardest Day: 18 August 1940. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1980

[1] Henry Probert, Bomber Harris: His Life and Times, (London: Greenhill Books, 2006), 98.

[2] James Holland, The Battle of Britain: Five Months that Changed History, May-October 1940, (New York: Macmillan, 2012), 443.

[3] Ibid., 101

[4] David Fischer, A Summer Bright and Terrible: Winston Churchill, Lord Dowding, Radar, and the Impossible Triumph of the Battle of Britain, (California: Counterpoint Press, 2006), 164.

[5] Holland, 450.

[6] Ibid., 327.

[7] Denis Richards and Hilary St. G. Saunders, Royal Air Force, 1939-1945. Vol I: The Fight at Odds, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953), 190-193 .

[8] Alfred Prince, The Hardest Day: 18 August 194, ( New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1980), 12.

[9] Ibid, 572.

[10] Robert Wright, The Man Who Won the Battle of Britain, (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1969), 25.

[11] Fischer, 34.

[12] Ibid., 36.

[13] Ibid., 75.

[14] George Clode, “Dowding and Park: Air War’s Greatest Commanders?,” http://www.military-history.org/articles/dowding-and-park-air-wars-greatest-commanders.htm (accessed April 16, 2013).

[15] Fischer, 72.

[16] Simon Braun, “The Command Style and Competence of Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Caswell Tremenheere

Dowding,” master’s thesis, University of Canberra, 2005, 3.

[17] Fischer, 63.

[18] Holland, 104.

[19] Clode.

[20] Holland, 327.

[21] Ibid., 347.

[22] Braun, 10.

[23] Fisher, 29.

[24] Ibid., 421.

[25] Holland, 559.

[26] Fisher, 137.

[27] Wright, 210.

[28] Stephen Bungay. The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain, (London: Aurum Press, 2000), 331.

[29] Wright, 226

[30] Ibid., 220.

One comment